By Joanna Puddister King

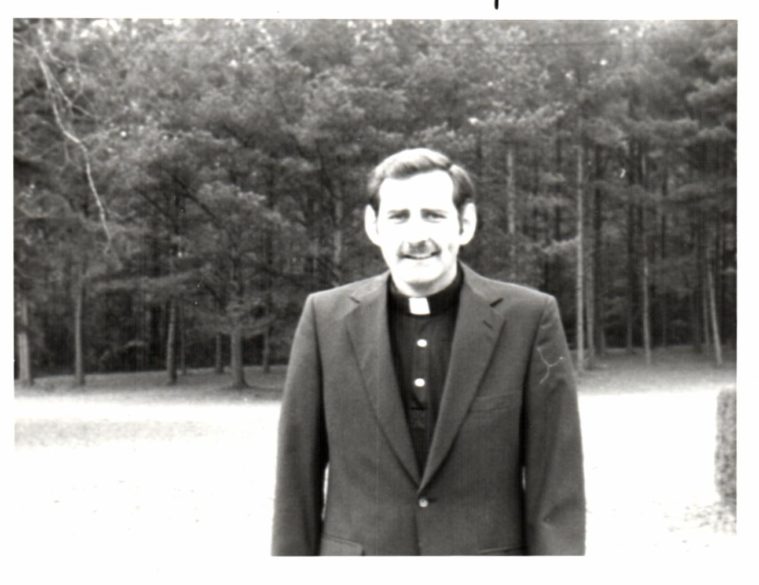

PHILADELPHIA – At 72 years old, Father Robert “Bob” Goodyear had much to reflect on for his nomination by the Diocese of Jackson for the Catholic Extension Lumen Christi award, that celebrates Christ’s call to service to his church. Father Goodyear truly demonstrates how the power of faith can transform lives – in his case, the Choctaw community.

When he first arrived on the Choctaw Reservation in 1975 as a newly ordained Missionary Servant priest, Father Goodyear described the “mission” as “having a church workday to cut firewood for the elderly and sick.”

“They were surprised I knew how to use a chainsaw and drive a tractor,” said Father Goodyear – a call back to his very first missionary assignment to Clay county, Kentucky to an Appalachian coal mining town, where he learned to use a chainsaw, dig a foundation by hand and other various construction skills.

In total, Father Goodyear has been assigned to Holy Rosary Indian Mission for 31 years, but not continuously. He served from 1975 to 1990, then was assigned to a mission in Tennessee, then to one in Magee. He returned to the Choctaw Reservation in 2006.

The reservation went through many changes while Father Goodyear was away at other missions. “The dirt roads were paved. There are two casinos that subsidize the tribal programs,” he said.

Roads and casino weren’t the only things that changed. When Father Goodyear first arrived in 1975, Choctaw was the primary language of 98% of the tribe and today that is only true of the elders. Now, most are bilingual.

In his early years at Holy Rosary Indian Mission – a group of three churches consisting of Holy Rosary in Philadelphia, St. Therese Mission in the Pearl River Community and St. Catherine Mission in Conehatta – Father Goodyear read everything he could to learn about the culture of the people he was charged with ministering to.

He eventually gained the trust of the Choctaw community and with the help of three Choctaws he was taught their language.

“As I was first learning Choctaw, I quickly learned there are seven dialects of Choctaw on the reservation and when speaking to someone I needed to know what Choctaw community they came from. Words have different meanings, sometimes very different, in different communities,” said Father Goodyear.

After eight years of studying the Choctaw language, Father Goodyear began translating the Mass into Choctaw with the help of his teachers and an elder, who was the recognized expert on the language. Then with the aid of the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions, Father Goodyear prepared the translation of the Mass to the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) and then to the Sacred Liturgy office in Rome.

Finally, after eight years with the mission, Father Goodyear was able to celebrate his first Mass in the Choctaw language on May 1, 1983 at St. Catherine Mission in Conehatta.

“The Choctaw language and culture are critical elements in Choctaw self-identity,” said Father Goodyear. “The role of the church here is to believe in the Choctaws, their giftedness, their beauty, their talents, their hopes, so they will believe in themselves as much as God believes in them.”

While his first assignment to Holy Rosary Indian Mission was characterized by “non-traditional” ministries, Father Goodyear learned and did the usual things an associate pastor would do – working with youth, faith education, marriage preparation and the like. When the sisters moved to their new convent building, he remodeled the old convent building and turned it into a recreation center for the youth.

With the Choctaws, he worked with the tribe every chance he could. He worked on a suicide counseling manual, a self-image study, the Choctaw Human Services Council, the Choctaw Most In Need Indian Children and Youth federal demonstration project, and with the Choctaw grant writing office to not only preserve their faith, but the culture and language of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians.

When he returned to the Holy Rosary Mission in 2006, Father Goodyear’s primary focus has been the preservation of the faith and the development of lay leadership in his three churches.

He developed a training manual for Eucharistic ministers that trains them not only to assist in Mass, but also how to lead a Sunday celebration in the absence of a priest and how to take the Eucharist to the sick and shut-ins – a resource used not only on the reservations, but also in other parishes around the diocese and even in parishes in other states.

As a staff of one, what Father Goodyear has accomplished is nothing less than remarkable. Not to mention, rising to the challenge of ministering during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic.

PEARL RIVER – Father Bob Goodyear stands with his 2020 Confirmation class. He has known each of them since birth, baptizing each of them as infants. Pictured left to right, Kelin Kelly, Sierra Wallace, Sydney Nickey, Father Goodyear, Katelin Williams, Onnahili Williams, Alexis Williams and Veronica Williams. (Photo by Bradley Isaac)

Reports have the percentage of Choctaws affected by the virus at about 18%. For a time, Father Goodyear was tending to two to four funerals per week. He has spent a great deal of his time on the phone, writing letters and messaging on Facebook to give his support to those who are grieving. “It is important to know that they are not forgotten and are prayed for,” says Father Goodyear.

He has also spent much time reaching out to those who have been afraid to come to church because of the virus and has worked along side the tribe encouraging Choctaws to take the vaccine.

As COVID restrictions begin to loosen, Father Goodyear is looking to recruit catechist and reaching out to the children and youth again. This Easter, he will baptize nine children at St. Catherine’s in Conehatta and has 15 young people and five adults in RCIC and RCIA. “While attendance is down in my other two churches, the Holy Spirit has been working overtime in Conehatta,” says Father Goodyear.

He says that his focus now is preparing the reservation to assume more responsibility for the future of their churches. “It is unusual for a priest to be in a place for so long. It was not my “plan,” but it has been a blessing I never expected. In spite of the demands of being a staff of one for three churches, I have never been happier as a priest or feel more blessed personally than I am today.”

(Each Lumen Christi Award nominee receives $1,000 in support of his or her ministry, and the award recipient is given a $50,000 grant, with the honoree and nominating diocese each receiving $25,000 of the grant money to enhance their community and ministry. The winner will be announced later in the year.)