IN EXILE

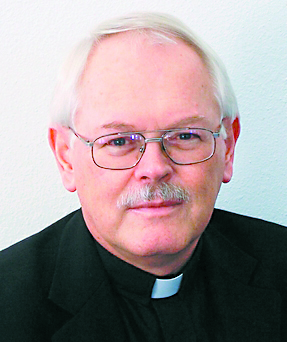

By Father Ron Rolheiser, OMI

It is not enough merely to have saints; we need saints for our times! An insightful comment from Simone Weil. The saints of old have much to offer; but we look at their goodness, faith, and selflessness and find it easier to admire them than to imitate them. Their lives and their circumstances seem so removed from our own that we easily distance ourselves from them.

So, I would like to propose a saint for our times, Stanley Rother (1935-1981), an Oklahoma farm boy who became a missionary with the poor in Atitlan, Guatemala, and eventually died a martyr. His life and his struggles (save perhaps for his extraordinary courage at the end) are something to which we can easily relate.

Who is Stanley Rother? He was a priest from Oklahoma who was shot to death in Guatemala in 1981. He has been beatified as a martyr and is soon to become the first male born in the United States to be canonized. Here, in brief, is his story.

Stanley Rother was born to a farming family in Okarche, Oklahoma, the oldest of four children. He grew up helping work the family farm and for the rest of his life and ministry he remained forever the farmer more than the scholar. Growing up and working with his family, he was more at home tilling the soil, fixing engines and digging wells than he was reading Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas. This would serve him well in his work with the poor as a missionary, though it served him less well when he first set out to study for the priesthood.

His initial years in the seminary were a struggle. Trying to study philosophy (in Latin) as a preparation for his theological studies proved a bit too much for him. After a couple of years, the seminary staff advised him to leave, telling him that he lacked the academic abilities to study for the priesthood. Returning to the farm, he sought the advice of his bishop and was eventually sent to Mount St. Mary’s Seminary in Maryland. While he didn’t exactly thrive there academically, he thrived there in other ways, ways that impressed the seminary staff enough that they recommended him for ordination.

Back in his own diocese, he spent the first years of his priesthood mostly doing manual work, redoing an abandoned property that the diocese had inherited and turning it into a functioning renewal center. Then, in 1978, he was invited to join a diocesan mission team that had begun a mission in Guatemala. Everything in his background and personality now served to make him ideal for this type of work and, ironically, he, who once struggled to learn Latin, was now able to learn the difficult language of the people he worked with (Tz’utujil) and become one of the people who helped develop its written alphabet, vocabulary and grammar. He ministered to the people sacramentally, but he also reached out to them personally, helping them farm, finding resources to help them and occasionally giving them money out of his own pocket. Eventually he became their trusted friend and leader.

However, not everything was that idyllic. The political situation in the country was radically deteriorating, violence was everywhere and anyone perceived to be in opposition to the government faced the possibility of intimidation, disappearance, torture and death. Stanley tried to remain apolitical, but simply working with the poor was seen as being political. As well, at a point, a number of his own catechists were tortured and killed and, not surprisingly, he found himself on a death list and was hustled out of the country for his own safety. For three months, back with his family in Oklahoma, he agonized about whether to return to Guatemala, knowing that it meant almost certain death. The decision was especially difficult because, while clearly he felt called to return to Guatemala, he worried about what his death there would mean to his elderly parents.

He made the decision to return to Guatemala, fired by Jesus’ saying that the shepherd doesn’t run when the sheep are in danger. Four months later, he was shot to death in the missionary compound within which he lived, fighting to the end with his attackers not to be taken alive and made “to disappear.” Instantly, he was recognized as a martyr and when his body was flown back to Oklahoma for burial, the community in Atitlan kept his heart and turned the room in which he was martyred into a chapel.

A number of books have been written about him and I highly recommend two of them. For a substantial biographical account, read Maria Ruiz Scaperlanda, The Shepherd Who Didn’t Run. For a hagiographical tribute to him read Henri Nouwen, Love in a Fearful Land.

We have patron saints for every cause and occasion. For whom or for what might Stanley Rother be considered a patron saint? For all of us ordinary people of whom circumstance at times asks for an exceptional courage.

(Oblate Father Ron Rolheiser is a theologian, teacher and award-winning author. He can be contacted through his website www.ronrolheiser.com.)