By Maureen Smith

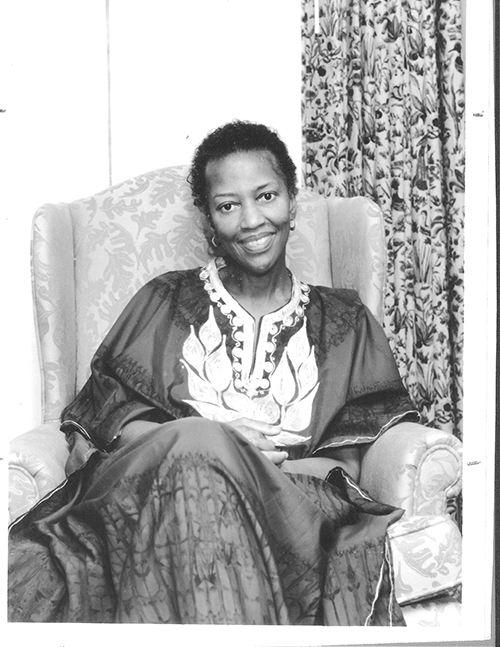

CANTON – There is no doubt that Sister Thea Bowman, FSPA, possessed a presence. Many of those who knew her well speak of how she enveloped those around her with love, encouragement and positive energy, no matter if they were a life-long friend or someone she just met. March 30 will mark 25 years since she died in the Canton home where she grew up. She was a trailblazer in almost every role — first black nun from Canton, first to head an office of intercultural awareness, first black woman to address the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB), but to those who grew up under her tutelage in Canton, she was a singular inspiration.

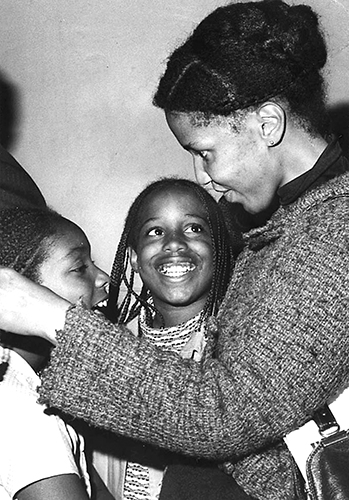

“Calling her an encourager – that’s not even a strong enough word,” said Cornelia Johnson, a student of Sister Bowman. “She was that person who went beyond seeing the good in every person. She helped that good come out more,” Johnson added. She spoke of how Sister Bowman seemed to know when a child was in need.

This week the editors at Mississippi Catholic asked some who knew her to reflect on her legacy and her call to evangelization. This issue also includes a Holy Week reflection she wrote weeks before her death.

Bertha Bowman was born in Yazoo City, the granddaughter of slaves, but daughter of a doctor and a teacher. She attended Canton Holy Child Jesus School, converted on her own at age eight and knew by her early teenage years that she was called to the consecrated life. Sister Bowman studied at Viterbo College in LaCrosse, Wisc., while preparing to enter the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration. She went on to study at Catholic University.

She returned to Canton to teach and inspire the people in her community. “I was proud to have her be from Canton,” said former student Myrtle Jean Otto. Otto said she not only demanded excellence from her students, she wanted them to think beyond traditional roles. “She was a wonderful person to be around because you learned a lot from her. She wanted you to go to college and learn,” said Otto. “If you were not college material, she would encourage you to get a good trade,” she added.

Both Otto and Johnson said the fact that Sister Bowman was from Canton was a huge part of why so many looked up to her, but they also spoke of her compassion. “She had more of an impact because she was black, and she let us know we could do anything we wanted to do,” said Otto. This influence was especially important as Canton, and the nation, struggled after the Civil Rights Movement to define new roles for black people in business, society and within the Catholic Church.

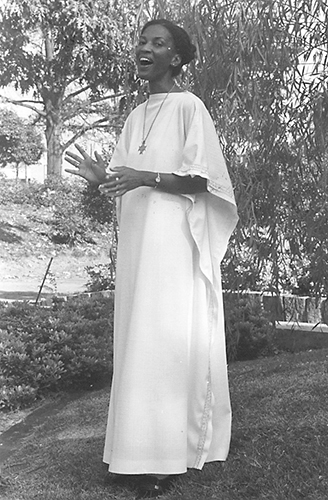

Sister’s education and background led her to reflect upon the tensions of race and culture within the Catholic Church. She became a unique evangelizer. She did not advocate for a uniform worship including parts of different cultures. She called on church leadership to recognize the value of all cultural contributions within the church, to let people express their faith within their own cultural context.

Sister Bowman personally experienced the struggle. Mary Queen Donnelly, a white woman who grew up in Canton and knew the Bowmans, expressed her version of Sister Bowman’s journey in a play to be staged in Madison in April. Donnelly described how Sister Bowman had to unite her black cultural background, with its characteristic music, storytelling, food and expressions, with the very conservative structures of the church. Bishop Brunini invited her to lead the Office of Intercultural Awareness for the Diocese of Jackson, but she didn’t stop there. She took her message across the nation, speaking at church gatherings and conventions. Music was especially important to her. She would gather or bring a choir with her and often burst into song during her presentations.

She invited church leaders to her hometown and immersed them in its culture. “She would call my mama and say, I have a guest coming, will you cook for me?” explained Otto. “And my mother would fix a meal for her, fried chicken with rice and gravy or gourmet biscuits or cornbread,” said Otto.

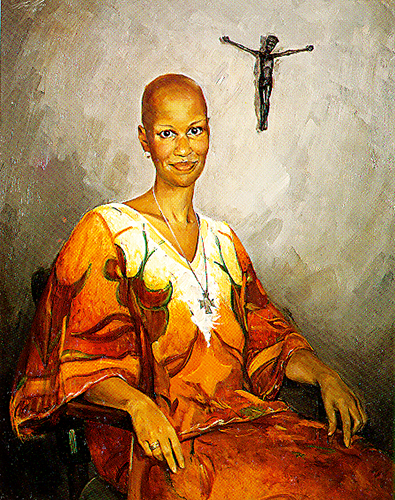

Sister Bowman got breast cancer at the height of her career. She continued her grueling travel schedule, even as the disease took her hair, her ability to speak and her strength. When Sister Bowman spoke at the USCCB gathering months before her death she was blunt. She told the bishops that people told her black expressions of music and worship were ‘un-Catholic.’ Sister Bowman challenged that notion, pointing out that the church universal included people of all races and cultures and she challenged the bishops to find ways to consult those of other cultures when making decisions. She told them they were obligated to better understand and integrate not just black Catholics, but people of all cultural backgrounds.

In a video of her appearance at the USCCB meeting, a crew of men lift her wheelchair onto the stage. She is wrapped in a blanket and slightly slumped over during the introductions. Once she is introduced, the blanket comes off. Sister Bowman begins singing and sits up straighter, drawing laughter and rapt attention as she gets more and more animated throughout the speech. At the end she orders the bishops to stand and sing ‘We Shall Overcome’ with her. They comply, even linking arms together to express their solidarity. Many in the video have tears in their eyes.

Otto said one of Sister Bowman’s talents was her ability to relate across social, racial and educational boundaries. “She could speak to everyone on their level, whether you had a college degree or were just a poor person,” said Otto. She and Johnson both said Sister Bowman had an uncanny ability to connect to people and challenge them. “I wanted to play the piano, but she discovered I can sing,” said Otto, who still sings for weddings, funerals and weekly liturgies.

“Because of her, I grew to be the woman I think God wanted me to be,” said Johnson. She credits Sister Bowman and Sister Antonia Ebo with saving her life. Johnson was in a terrible car accident. When she arrived at the hospital she was blind and could not speak because of a tracheotomy. “In my mind, I could see Sister Thea (Bowman) singing in front of a large choir. She was singing ‘hold on, just a little while longer,’” said Johnson. “I tell you – ‘hold on’ got me through,” She said Sister Ebo came and prayed with her daily as well.

“When Sister Thea (Bowman) came back from the meeting of the Black Catholic Congress she walked in my room and took my hand and I knew at that moment I would walk out of that hospital and I would be fine. I felt her love when she touched me,” said Johnson. When Johnson did return home, she began acting as an assistant to Sister Bowman, taking her phone calls while the nun traveled all around the nation delivering speeches, singing and bringing her message to the church. “This little light of mine” was one of Sister Bowman’s favorite songs. Those who knew her all said she would want her legacy to be one of continuing encouragement. Otto, Johnson and Donnelly all said Sister Bowman only wanted people to do their best – to follow their vocations to the best of their abilities – to be the best nurse, the best mother, the best Christian they could be, a worthy challenge indeed.

RELATED ARTICLES

- Sr. Thea: scholar, teacher, famous black woman

- Bishop remembers Sister’s patient enthusiasm

- Local Events Honoring Sister Bowman

- Local Sister Thea Bowman School carries on mission

- Franciscan Sisters announce events to honor Sister Bowman

- ‘Let us love one another,’ Sister Bowman’s Holy Week reflection