From the Archives

By Mary Woodward

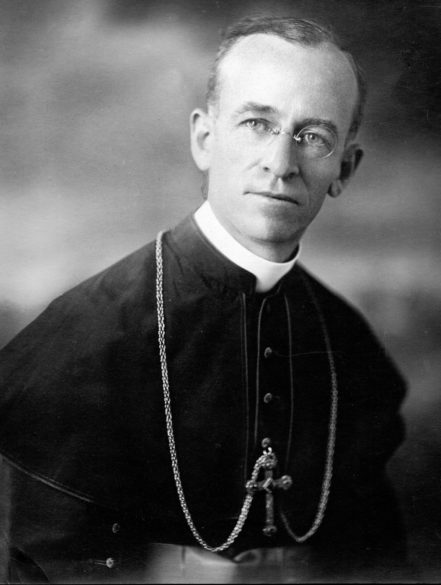

JACKSON – As we begin the new calendar year, let’s visit another interesting stop in Bishop John Gunn’s diary. This time we are on the road in northeast Mississippi in June of 1912.

On this trip, Bishop Gunn visits Tupelo and Plantersville among other places. He conferred the sacrament of confirmation and spoke to large gatherings of Catholics and non-Catholics in each location.

On June 12 he arrived in Tupelo and here is what he had to say about his visit: “Tupelo is a boom town of new growth with plenty of activity, and a promise that it may become something. The town hall was secured, much free advertisement was given, and I said Mass on the stage, confirmed a few Catholics there and found the big event of the visit was to be a mass meeting in the theatre to hear the Bishop talk of Catholic claims.”

“I spoke about an hour in Tupelo on that night and was congratulated for nearly another hour afterwards with such vigorous handshaking that I was afraid of arm dislocation.”

From Tupelo, Bishop Gunn headed the next day to Plantersville – called Potato Hill by locals. There he encountered an elderly Mrs. Kelly, who was overcome with tears of joy to meet the Bishop. Bishop Gunn’s diary account gives the reason for her outpouring.

“There was one family of the name Kelly – the oldest settler in that section – and after walking, riding and climbing for a number of hours we reached the little log cabin on a hill where Mrs. Kelly was rocking herself in expectation.”

“She was old and very religious and as soon as she heard that there was actually a Bishop on her porch she commenced to weep and to talk about John. ‘Do you think, Bishop, he will ever be forgiven, or what part of hell is he in, or can you get him out?’ Or other questions equally hard to answer.”

“I thought that John probably had misconducted himself in years gone by – he was now eleven years dead – and his wife had not completely forgiven him. I tried to make the man’s excuse as well as I could, but she would talk of John and finally I let her tell the whole story.”

“John and I came from Ireland to Mobile and we got married there and struck out to find a quiet place to spend our honeymoon. We got tired just here and we camped and thought it would be a good place to remain.”

“The Indians were everywhere but they didn’t bother us. John – who was a carpenter – cut down the logs and I was strong enough to drag the logs up here. John and I built this log house, and we were the happiest people in the world for some thirty or forty years. The Indians roundabout didn’t bother us, but the Protestants wanted me and John to go to their meeting houses, or they wanted us to pray with them.”

“This made John mad and every time he saw anything like a preacher he commenced to curse and swear, and I had great trouble in keeping John from attacking the preacher. This kept on for years and finally the great trouble came to John one evening when two men came up the side of the hill on horseback. John and I were on the porch looking at them coming.”

“John whispered to me ‘here are two more preachers’ and it was not long until one of them came up and said, ‘Aren’t you John Kelly?’ He said ‘Yes, what do you want?’ “Well, John, I heard you are a Catholic.’”

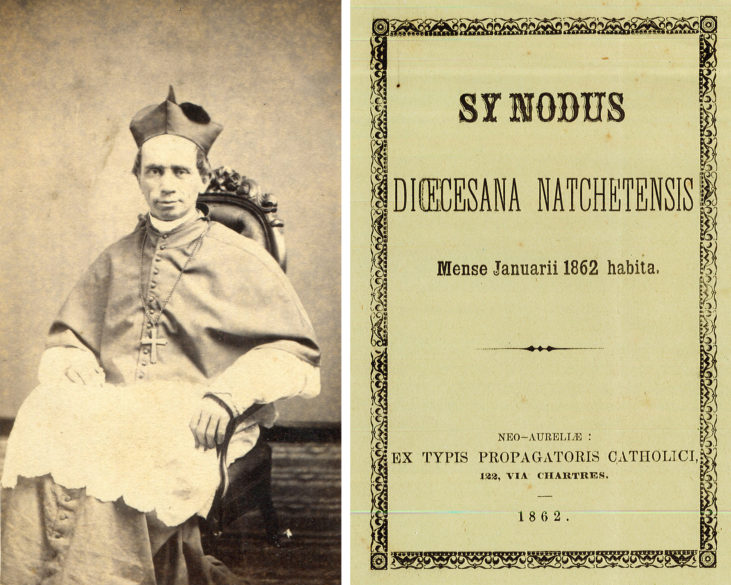

“Then John got mad, and he asked the preacher what in —- did it matter to him, and the preacher smiled, and that made John madder and madder. He told the preacher to go to the bad place. This made the man get off his horse and John got ready to thrash him when the preacher said to him: ‘Why, John Kelly, I am Bishop Elder, the Bishop of Natchez, and that is the way you receive me and treat me.’”

“Poor John was dumbfounded that he couldn’t speak but fainted. To send his Bishop, who had come 28 miles on horseback to see him – to welcome him in such a way. And Mrs. Kelly’s whole trouble was to find out if poor John, who had received the last Bishop who had visited them, was still suffering from the reception given.”

“The Kelly’s had been visited 28 years before by Bishop Elder and poor Mrs. Kelly was glad to see another Bishop who promised all kinds of excuses for her old man, John.”

“She had a number of grown-up children and their families. They were all at supper in the log cabin at Potato Hill. I got the best room and enjoyed it as the trip was long and tiresome.”

This is a great account of life on the road in our diocese. We take for granted being able to travel most places in the diocese in one day. Here we have the accounts of bishops travelling to some outlying areas to find their sheep – even sheep who greet them in a not so pleasant way.

God bless the Kelly’s of Potato Hill – salt of the earth.

(Mary Woodward is Chancellor and Archivist for the Diocese of Jackson)