IN EXILE

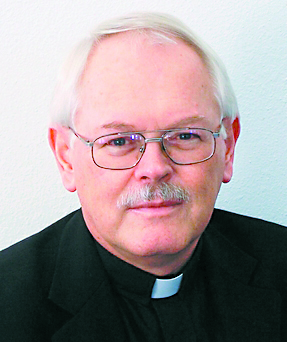

By Father Ron Rolheiser, OMI

I once lived in community for several years with an Oblate brother who was wonderfully generous and pious to a fault. But he struggled to pick up symbol and metaphor. He took things literally. For him, what the words said is what they meant!

This caused him considerable confusion and consternation when each day praying the psalms we would pray for Jerusalem and Israel and would occasionally pray for the demise of some other nation. Coming out of prayer, he would ask: “Why are we praying for Jerusalem? For Israel? What makes those places more special in God’s eyes than other cities and other countries? Why does God hate some countries and cities?”

We would try our best to have him understand that these names were not to be taken literally, as places on a map, but rather as symbols. Wisely or unwisely, I would sometimes say, “Brother, whenever you read the word ‘Jerusalem’ or ‘Israel’, just take that to mean the ‘church’, and whenever a nation or a city is named that God seems to hate, take that to mean that God hates sin.”

We might smile at his piety and literalism, but I’m not sure we don’t all still struggle with our own literalism in understanding what in fact the scriptures mean by words like Jerusalem, Israel, Chosen people, and God’s elect. Indeed, as Christians, what do we mean with the words Christian, Church, and Body of Christ?

For whom are we praying when we pray for Jerusalem and Israel?

What we see in scripture is a progressive de-literalizing of names and places. Initially, Israel meant an historical nation, Jerusalem meant an historical city, the Chosen People meant a genetic race, and God’s elect was literally that nation, that city, and that genetic race. But as revelation unfolds, these names and concepts become ever more symbolic.

Most parts of Judaism understand these words symbolically, though some still understand these words literally. For them, Jerusalem means the actual city of Jerusalem, and Israel means an actual strip of land in Palestine.

Christians mirror that. Mainstream Christian theology has from its very origins refused to identify those names and places in a way where (simplistically) Jerusalem means the Christian Church and Christians are the Chosen Race. However, as is the case with parts of Judaism, many Christians, while de-literalizing these words from their Jewish roots, now take them literally to refer to the historical Christian churches and to its explicitly confessing members. Indeed, my answer to my Oblate brother (“Jerusalem means the church, Israel means Christianity”) seems to suggest exactly that.

However, the words Church and Christianity themselves need to be de-literalized. The church is a reality which is much wider and more inclusive than its explicit, visible, baptized membership. Its visible, historical aspect is real, is important, and is never to be denigrated; but (from Jesus through the history of Christian dogma and theology) Christianity has always believed and taught clearly that the mystery of Christ is both visible and invisible. Partly, we can see it and partly we can’t. Partly it is visibly incarnated in history, and partly it is invisible. The mystery of Christ is incarnate in history, but not all of it can be seen. Some people are baptized visibly, and some people are baptized only in unseen ways.

Moreover, this is not new, liberal theology. Jesus himself taught that it is not necessarily those who say ‘Lord, Lord’ who are his true believers, but rather it’s those who actually live out his teaching (however unconsciously) who are his true followers. Christian theology has always taught that the full mystery of Christ is much larger than its historical manifestation in the Christian churches.

Kenneth Cragg, a Christian missionary, after living and ministering for years in the Muslim world, offered this comment: I believe it will take all the Christian churches to give full expression to the full Christ. To this, I would add, that it will not only take all the Christian churches to give full expression to the mystery of Christ, it will also take all people of sincere will, beyond all religious boundaries, and beyond all ethnicity, to give expression to the mystery of Christ.

When my pious Oblate brother who struggled to understand metaphor and symbol asked me why we were always praying for Jerusalem and Israel, and I replied that he might simply substitute the word Church and Christianity for those terms, my answer to him (taken literally) was itself over pious, simplistic, and a too-narrow understanding of the mystery of Christ. Those terms Church and Christianity, as we see in the progressive unfolding of revelation in scripture, must themselves be de-literalized.

For whom are we praying when we pray for Jerusalem or for Israel? We are praying for all sincere people, of all faiths, of all denominations, of all races, of all ages. They are the new Jerusalem and the new Israel.

(Oblate Father Ron Rolheiser is a professor of spirituality at Oblate School of Theology and award-winning author.)