IN EXILE

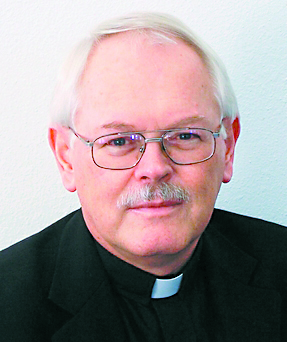

By Father Ron Rolheiser, OMI

I am sure many of you are familiar with the TV series about the life of Jesus called The Chosen. It was launched in 2019, has been in theaters and on streaming platforms since, and now has more than 200 million viewers. It has been translated into 50 languages and has 13 million social media followers, with about 30 percent of its audience being non-Christian.

It was created and produced by Dallas Jenkins, an Evangelical Christian with wide ecumenical and interfaith sympathies. Jonathan Roumie, a devout Roman Catholic, plays the role of Jesus, and the Jesus he portrays in The Chosen comes through as somewhat different from, and more relatable to, than the Jesus we have generally seen in other movies and portrayals of him. And this has had an interesting impact.

What’s the impact? Joe Hoover, a Jesuit priest writing in a recent issue of America magazine, makes this comment: “I have been a baptized Christian for 53 years, attended a Catholic Christian grade school and for more than two decades have been a member of a religious order that bears the name of Jesus … and ‘The Chosen’ television series had done things for my understanding and engagement with the life of Christ and his disciples that nothing else has. No sermon, no theological exhortation, no master’s degree, no class on John or Mark or Luke, no spirituality workshop, no 30-day biblically based retreat has brought the Gospels home and made Christ and his people real and relatable to me in quite the way ‘The Chosen’ has.”

That speaks for me as well. The Chosen has had a similar effect on me. Like Joe Hoover, I was baptized as an infant, raised a Roman Catholic, am a member of a religious order, have degrees in theology, have been to every kind of spirituality workshop, and have studied the Gospels under the guidance of some world class scholars, and yet this TV series has given a face to Jesus that I didn’t quite receive in all that past learning and has helped me in my prayer and my relationship to Christ.

In essence, this is what The Chosen has done for me. It has presented a Jesus whom I actually want to be with. Shouldn’t we always want to be with Jesus? Yes, but the Jesus who is often presented to us is not someone, if we are honest with ourselves, we would want to spend a lot of one-on-one time with, with whom we could be at ease and comfortable without affectations.

For instance, the Jesus who has often been presented to us in movies is generally lacking in human warmth, is distant, stern, other-worldly, over pious, and whose very gaze makes you feel guilty because your sin caused his crucifixion. That Jesus is also humorless, doesn’t ever seem to bring God’s smile to the world, and never brings any lightness into a room. He is not a Jesus with whom you are at ease.

Unfortunately, that is often the Jesus who has been presented to us in our preaching, catechesis, Sunday schools, theological classes and in popular spirituality. The Jesus we meet there, for all the truth and revelation he brings into the world, is generally still too divine and overly pious for us to be at ease with humanly. He is a Jesus we admire, perhaps even adore, and whom we trust enough to commit our lives to (no small thing). But he is also a Jesus with whom we are not much at ease, whom we wouldn’t pick to sit next to at table, with whom we wouldn’t pick to go on vacation, and who is so distant and distinct from us that it is easier for us to have him as an admired teacher than as an intimate friend, let alone as a lover to whom we want to bear our soul.

This is not a plea to humanize Jesus (as is sometimes in fashion today) by making him just a nice man who preaches love but doesn’t at the same time radiate God’s non-negotiable truth. This is not what The Chosen does. Far from it.

The Chosen presents us with a Jesus whose divinity you never doubt, even as he appears as warm and attractive, with a humanity that puts you at ease in his presence; indeed, it lures you into his presence. Watching The Chosen, one never doubts for an instant that Jesus is specially and inextricably linked to his Father and that he brings us God’s truth and revelation without compromise. But this Jesus also brings God’s smile, God’s warmth and God’s blessing upon our lives which too often suffer from a lack of these.

The great mystic Julian of Norwich once described God is this way: God sits in heaven, completely relaxed, his face looking like a marvelous symphony.

Among other things, The Chosen shows us this relaxed face of God, which to our own detriment we too seldom see.

(Oblate Father Ron Rolheiser is a theologian, teacher and award-winning author. He can be contacted through his website www.ronrolheiser.com.)