By Father Nick Adam

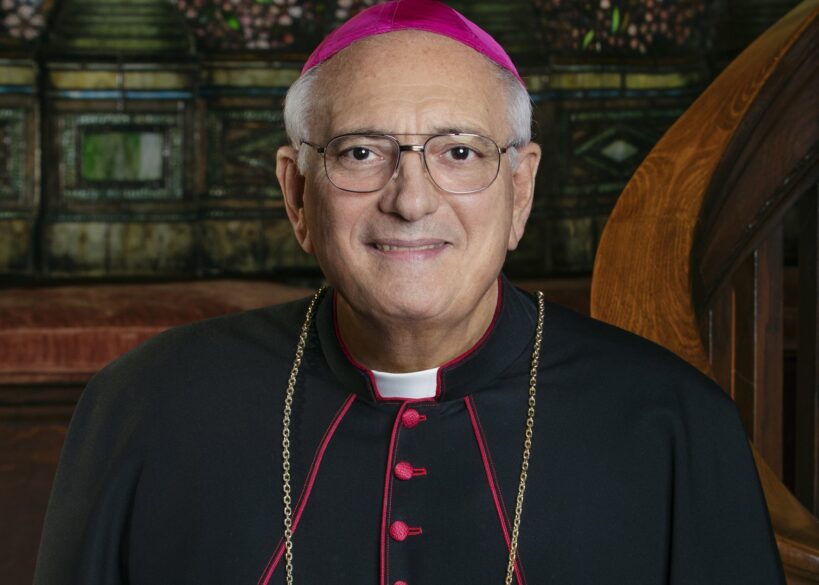

Father Tristan Stovall, Bishop Joseph Kopacz and I enjoyed a wonderful visit to Notre Dame Seminary in late September for the final faculty evaluation for Will Foggo. Will began his journey through seminary formation back at the very height of the pandemic in August 2020. I was blown away by his courage and perseverance to join the seminary at such a challenging time.

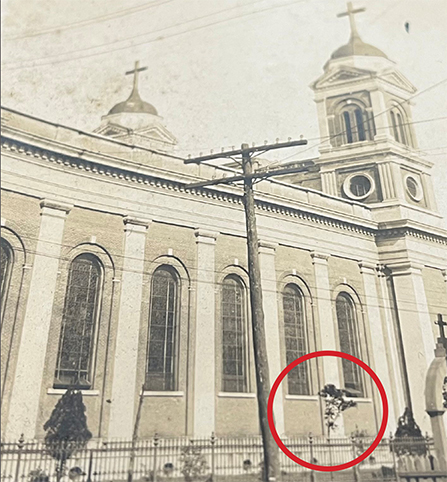

Now, five years later, Will is completing his classwork and, after his evaluation, is officially recommended to be admitted to the Sacrament of Holy Orders. He will be ordained a deacon on Saturday, Nov. 29, at the Cathedral of St. Peter the Apostle at 10:30 a.m., and he will be ordained a priest on Saturday, May 16, 2026 after a six-month period of work as a deacon in a parish.

There are three levels of holy orders: deacon, priest, and bishop. A man must be a deacon before he is ordained a priest, and a priest before he is ordained a bishop. As a deacon, the man is blessed with sacramental grace to act in the person of Christ the servant, while the priest is ordained to act in the person of Christ the priest. The bishop receives the fullness of holy orders and acts as the shepherd of the whole diocese. Of course, bishops and priests don’t ‘stop’ being deacons after ordination. They must lead and sanctify the people with a servant’s heart, and they will need to draw on the graces of the sacrament in order to be faithful to their duty for life.

So, it was a joyful evening at Notre Dame Seminary following Will’s evaluation. We gathered in the ‘Bib,’ short for bibliotheca (Latin for ‘library’), which is the hangout area for the seminarians ‘after hours.’ Father Tristan cooked a wonderful meal that we all enjoyed, and I love seeing our seminarians, veterans and rookies, having a great time together.

I mentioned to the rector of the seminary, Father Josh Rodrigue, who joined us for the meal, that I always dreamed that we could have a gathering like this one. I cherished my time with my own diocesan brothers in the seminary, but to see so many Jackson men together and having a great time gathered around their bishop was very moving to me.

Our discernment groups are launching once again for the fall semester, and the vocation team is inviting men to take part in a group, visit the seminary, or both. My discernment group in Jackson began the first week of October, and I’m planning on taking at least three men down to St. Joseph Abbey to visit the seminary on Columbus Day weekend. Five discernment group participants from last year ended up in the seminary this year, so this is a model of accompaniment that is repeatable and works.

We are focusing this year on encouraging visits to the seminary as they seem to have the greatest impact on the men. I always remind the guys — we do not offer these opportunities to force them to become priests, but we are giving them resources to explore the call. We see potential in them, yes, but they cannot make a free choice for the Lord if they never get to speak to anyone about what priesthood is like or what the seminary entails. Please keep these discerners in your prayers and pray that the Lord continues to bless us with more seminarians who desire, like Will, to be servant leaders in our diocese.

(For more information on vocations, visit jacksonvocations.com or contact Father Nick at nick.adam@jacksondiocese.org.)