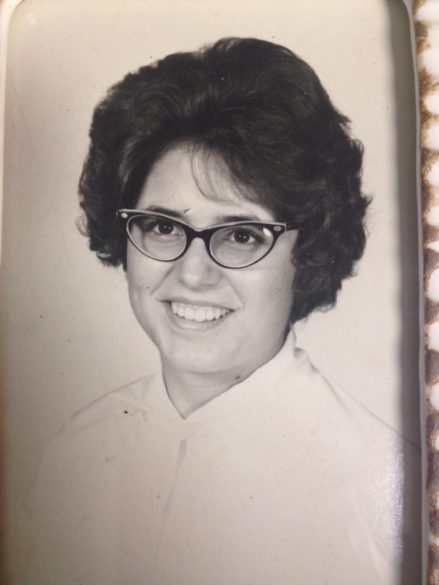

Mother’s Day snuck up on me I must admit, it feels like we are usually well into the double-digit days of May before we set aside a day to honor Mom. I’m sitting here at my desk remembering the many lessons my mom taught me, at home, at school and in the church. My mother was my elementary school principal. I attended St. Benedict School in Elberta, Alabama where Claudia Adam was the principal from 1995-2005. It’s not every kid who can say that his mom literally ‘taught him.’

Because mom was a Catholic School teacher, she had plenty to do with the life of the parish. St. Bartholomew Parish sits right across the street from St. Benedict, and my mom cared deeply about enriching the faith of all the students under her care. With the help of handymen in the community she converted an old storage room into a very nice chapel on the school campus, and she never missed an opportunity to talk to us students about the importance of Mass and other devotions that we took part in like Stations of the Cross during Lent. I still remember that we would sing the parts of the Stabat Mater in Latin, we sounded like angels, except for being out of tune! My mother’s example was a huge reason that I became a priest. I saw her life of service, and it spoke to me.

So, this is my encouragement to all you moms out there who have sons that are the apple of your eye. Please encourage them if you see priestly gifts in them. I know it can be frightening and different for your child to choose a road less traveled but take Mary’s example to heart. Mary had one child, and that child was miraculously conceived. Mary had a choice, and she said yes. And that yes blessed not just her family, not just her people, not just her country, not just the world, but the universe. That ‘yes’ brought Jesus into the world. God could have done it another way, but he allowed a free choice to bring Jesus into the created order. Your ‘yes’ can bless the universe as well. Your ‘yes’ can help Jesus be made sacramentally present in a parish that doesn’t have a resident priest right now. And we don’t just need more priests, we need more good priests. We need good men from good families who could serve their community and the world doing anything because they are so talented, but they choose to serve the church because they were called to this vocation, and they were nurtured and encouraged by their family to be generous with their gifts for the salvation of souls.

Moms have a lot to do with a good man choosing to serve the church as a diocesan priest, and they can also have a lot to do with steering a man away from that call. I know it is scary, but I promise to do my best to walk with you and your family on the journey. I am so grateful to the mothers of our current seminarians who, like Mary, said yes. And their yes will lead to Jesus being made present in the sacraments for decades to come. In your charity, please say a prayer for my mom, who died in 2014. I miss her, but her example of humble service still inspires me, and even though she died before I was ordained, her courageous witness helped me to say yes to the Lord when the time came. Blessings to all moms and mother figures!

– Father Nick Adam

If you are interested in learning more about religious orders or vocations to the priesthood and religious life, please email nick.adam@jacksondiocese.org.