Dear Friends in Christ,

I write the year in review after just having celebrated three Masses and Fiestas in honor of Nuestra Senora de Guadalupe. Her feast day is Dec. 12, near and dear to me, because on this day six years ago I was announced as the 11th Bishop of the Diocese of Jackson.

Gracias a Dios! 2019 has been rich in ministry and blessings which have far surpassed the burdens and struggles of our times. Throughout the diocese many labor on behalf of the Lord to serve others, to inspire disciples and to embrace diversity which is our diocesan vision statement. Daily we inspire from our pulpits and by the witness of our lives; we serve in our schools, through Catholic Charities, and in our parishes; we embrace diversity, stirred by the Gospel imperative to gather people as a counterweight to the polarization in our country that scatters.

The Church’s mission was evident in the aftermath of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids in August in several communities in our diocese. Generosity poured in from all over the country, and agencies throughout Mississippi entrusted to Catholic Charities the mission of assisting the families who were devastated by the round ups. Finally, as important as any ministry, we remain vigilant in providing a safe environment for our children and young people and steadfast in our commitment to help those broken by sexual abuse.

2019 also had distinctive opportunities for travel abroad, so to speak.

In February I embarked on a pastoral visit to India for two weeks. Why, you might ask? Thirteen of our 70-75 active priests serving in the Diocese of Jackson are from India. Try to imagine a country about the size of ours with a billion more people. It was intense and inspiring.

In July our diocese marked the 50th anniversary of our mission in Saltillo, Mexico. It was festive and joyful to be with the people of Northeast Mexico for this milestone, a solidarity in Jesus Christ that has been mutually enriching for many this past half century.

In December I and the bishops of our region went to Rome for one week on what is called the Ad Limina Apostolorum, a required pilgrimage for every bishop around the world every 5-7 years to renew our unity with the Church and the successor of Saint Peter. After visiting the tombs of Saint Peter and Saint Paul 40 bishops gathered with Pope Francis for 2.5 hours of dialogue. This was exhilarating and edifying. Our Catholic Church is truly worldwide!

In the midst of all that life sends our way, may we be always mindful that the Light of the World shines in the darkness, full of grace and truth, and the darkness cannot overcome Him.

Come, Lord Jesus! Merry Christmas! God’s peace!

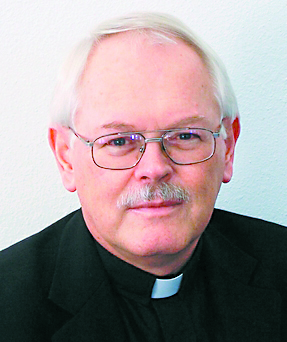

+Bishop Joseph Kopaz

but still mobile once he gets moving, and assures

you that 20 hours of rest and sleep per day is just

what the Vet prescribes.