IN EXILE

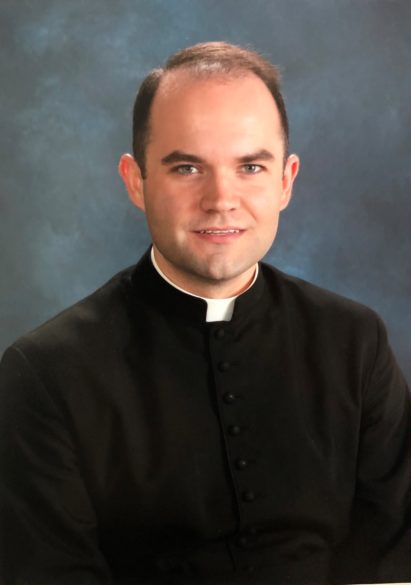

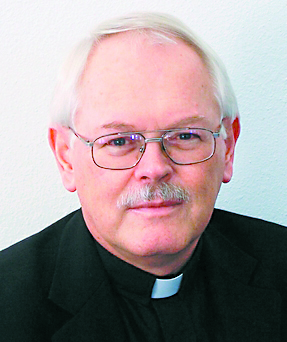

By Father Ron Rolheiser, OMI

We live in a culture that idealizes youth and marginalizes the old. And, as James Hillman says, the old don’t let go easily either of the throne or the drive that took them there. I know; I’m aging.

For most of my life, I’ve been able to think of myself as young. Because I was born late in the year, October, I was always younger than most of my classmates, graduated from high school at age seventeen, entered the seminary at that tender age, was ordained to the priesthood at age twenty-five, did an advanced degree within the next year and was teaching graduate theology at age twenty-six, the youngest member on the faculty. I was proud of that, achieving those things so early. And so I always thought of myself as young, even as the years piled up and my body began to betray my conception of myself as young.

Moreover, for most of those years, I tried to stay young too in soul, staying on top of what was shaping youth culture, its movies, its popular songs, its lingo. During my years in seminary and for a good number of years after ordination, I was involved in youth ministry, helping give youth retreats in various high schools and colleges. At that time, I could name all the popular songs, movies, and trends, speak youth’s language and I prided myself in being young.

But nature offers no exemptions. Nobody stays young forever. Moreover, aging doesn’t normally announce its arrival. You’re mostly blind to it until one day you see yourself in a mirror, see a recent photo of yourself or get a diagnosis from your doctor and suddenly you’re hit on the head with the unwelcome realization that you’re no longer a young person. That usually comes as a surprise. Aging generally makes itself known in ways that have you denying it, fighting it, accepting it only piecemeal and with some bitterness.

But that day comes round for everyone when you’re surprised, stunned, that what you are seeing in the mirror is so different from how you have been imagining yourself and you ask yourself: “Is this really me? Am I this old person? Is this what I look like?” Moreover you begin to notice that young people are forming their circles away from you, that they’re more interested in their own kind, which doesn’t include you and you look silly and out of place when you try to dress, act and speak like they do. There comes a day when you have accept that you’re no longer young in in the world’s eyes – nor in your own.

Moreover gravity doesn’t just affect your body, pulling things downward, so too for the soul. It’s pulled downward along with the body, though aging means something very different here. The soul doesn’t age, it matures. You can stay young in soul long after the body betrays you. Indeed we’re meant to be always young in spirit.

Souls carry life differently than do bodies because bodies are built to eventually die. Inside of every living body the life-principle has an exit strategy. It has no such strategy inside a soul, only a strategy to deepen, grow richer and more textured. Aging forces us, mostly against our will, to listen to our soul more deeply and more honestly so as to draw from its deeper wells and begin to make peace with its complexity, its shadow and its deepest proclivities – and the aging of the body plays the key role in this. To employ a metaphor from James Hillman: The best wines have to be aged in cracked old barrels. So too for the soul: The aging process is designed by God and nature to force the soul, whether it wants to or not, to delve ever deeper into the mystery of life, of community, of God and of itself. Our souls don’t age, like a wine, they mature and so we can always be young in spirit. Our zest, our fire, our eagerness, our wit, our brightness and our humor are not meant to dim with age. Indeed, they’re meant to be the very color of a mature soul.

So, in the end, aging is a gift, even if unwanted. Aging takes us to a deeper place, whether we want to go or not.

Like most everyone else, I still haven’t made my full peace with this and would still like to think of myself as young. However I was particularly happy to celebrate my 70th birthday two years ago, not because I was happy to be that age, but because, after two serious bouts with cancer in recent years, I was very happy just to be alive and wise enough now to be a little grateful for what aging and a cancer diagnosis has taught me.

There are certain secrets hidden from health, writes John Updike. True. And aging uncovers a lot of them because, as Swedish proverb puts it, “afternoon knows what the morning never suspected.”

(Oblate Father Ron Rolheiser, theologian, teacher and award-winning author, is President of the Oblate School of Theology in San Antonio, Texas.)