From the Archives

By Mary Woodward

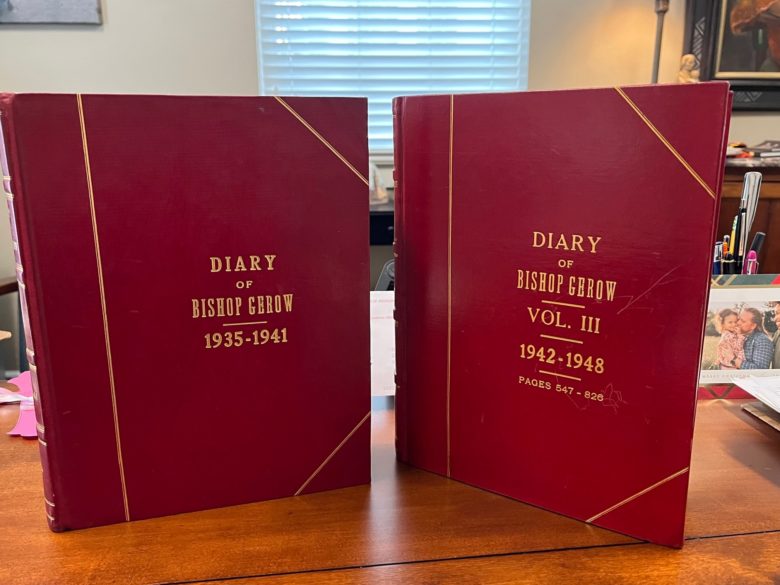

JACKSON – Considering the volatile situation, the world is facing, I thought I would share some more somber notes from Bishop John E. Gunn’s diary about World War I and a reflective paragraph from Bishop Richard Gerow’s diary on the beginning of World War II.

WWI was the war to end all wars, but obviously that was not the case. My paternal grandfather served as a mule-trainer in WWI as part of the 39th Infantry 140th Field Artillery Regimen in France during the last stages of that war. He never spoke of it.

Bishop Gunn writes in his diary at Christmas 1915: “It seemed hard to preach on peace on earth and good will to men at Christmas when everyone was talking of the big war. I made no allusion to it in my notes of 1915 because our President told us to be neutral in thought and word.

“However, now everybody is talking of it – in fact, the world is talking of nothing else, it may be no harm to note some dates and facts that will live in history.”

“In the summer of 1914, an Austrian Archduke was assassinated in Servia. The crime was an atrocious one and was turned over to the world politicians for adjustment. The politicians fumbled and turned the crime over to the war lords of Europe, with this result:

1914 – July 28th Austria declares war on Servia

August 1st Germany invades France

August 4th England declares war on Germany

August 6th The Germans take two Belgian forts

August 10th France breaks with Austria

August 13th England declares war on Austria

August 18th English soldiers land in France

August 23rd The Allies take offensive against the Germans along 150 miles from Mons to Luxembourg but on the 24th the Allies were forced to fall back. The Germans had all the initial advantages and on August 30th the French left wing had to fall back, thus exposing on August 31st even the capture of Paris; the French government voted to move the capital temporarily to Bourdeaux.”

“Apart from the Battle of Marne the first few months of the war was entirely favorable to Germany. Americans read and listened and the biggest propaganda that was ever known in the history of the world was started in 1914 and continued all through 1915 to get the Americans actively interested on the side of the Allies. In this diary I shall say little about the war, except where the Diocese took some part in it.”

On April 2, 1917, the United States entered the war on the side of the allies. It was the beginning of Holy Week in the Catholic Church and Bishop Gunn writes the following in his diary from April 1917: “The usual routine of Holy Week at Natchez – the blessing of the oils, the washing of the feet, the big ceremonies of Good Friday and Holy Saturday and Easter were all thrown in the shade by the declaration of war against Germany.

“This declaration upset everyone and everything and its influence was felt in every circle. I made up my mind before Easter Sunday the role that I would play as Bishop of Natchez during the war.”

“I had no time for consultation with anybody but at the Pontifical High Mass on Easter Sunday, April 8, I declared my policy very clearly and very plainly. While preaching on the subject ‘Christianity is not a Failure’ (because it never got a chance) as we were living in an age when there was knowledge without faith, manners without morality; plenty of work but ill-directed, I took up the President’s proclamation and told the Catholics of the Diocese that during the war they had to follow one leader; they had to form their conscience to one direction and to do everything as men, as Christians and as Catholics to win the war.”

Twenty-two years later, on Sept. 3, 1939, Bishop Gerow writes this bleak entry in his diary: “Today, England and France officially declared a state of war exists with Germany. Though we in this country are three thousand miles from Europe, we feel that the inauguration of another great war in Europe cannot but have a vital influence upon us and upon the other nations of the world, no matter how far away they may be.”

“We cannot but hope and pray that the other nations of the world will not be involved in this conflict and that another world war may not ensue which might wreck our modern civilization.”

Only two years later, he writes on Dec. 8, 1941: “Today, President Roosevelt addressed Congress telling them of the attack of the Japanese upon the Hawaiian Islands and our naval and air forces there, asking them to declare war.”

Bishops’ diaries provide a unique lens on history often including facts that do not make it into the history books. We are fortunate to have these diaries to be able to look back on the development of the church in Mississippi, the region, the country and the world.

I share these sobering passages from the two diaries to put into perspective what is going on in Ukraine as this is written. Who knows what will be by the day this is published and where we may be in two weeks or even two years? We can only pray and hope for peace.

(Mary Woodward is Chancellor and Archivist for the Diocese of Jackson.)