School is back in gear

By Joanna Puddister King

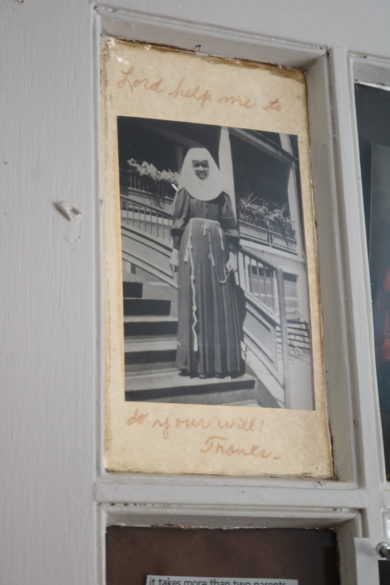

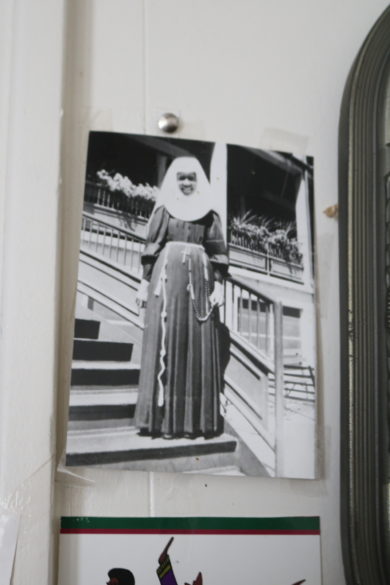

CANTON – New Group Media out of South Bend, Indiana is working to tell the story of Sister Thea Bowman. Filming is taking place in many locations where Sister Thea Bowman lived and worked, requiring in-depth work for both crew and community members.

Writer and producer, Sister Judy Zielinski, OSF said that she wanted to touch base and operate out of the spaces that Sister Thea lived in and used. “She was a brilliant, charismatic, prophetic, outspoken woman,” said Sister Judy during an interview. “And she is a force of nature.” Spaces chosen for filming include sites in Canton, Jackson, Memphis, New Orleans and in LaCrosse, Wisconsin.

The film will explore Sister Thea’s life and path to sainthood through interviews and commentary from her family, sisters in community, colleagues, friends and former students. While filming in Mississippi, the crew filmed interviews with Bishop Joseph Kopacz, and those that knew Sister Thea personally, including Sister Dorothy Kundinger, FSPA; former students, Myrtle Otto and Cornelia Johnson; and childhood friends, Mamie Chinn and Flonzie Brown-Wright.

The crew began scouting sites in April 2021 and at the end of May, they filmed in Canton, Jackson and at Sister Thea’s grave site in Memphis at Elmwood Cemetery. In addition to interviews, scenes were filmed depicting young Bertha Bowman’s life before entering the Franciscan Sisters of Perpetual Adoration (FSPA) in LaCrosse, Wisconsin.

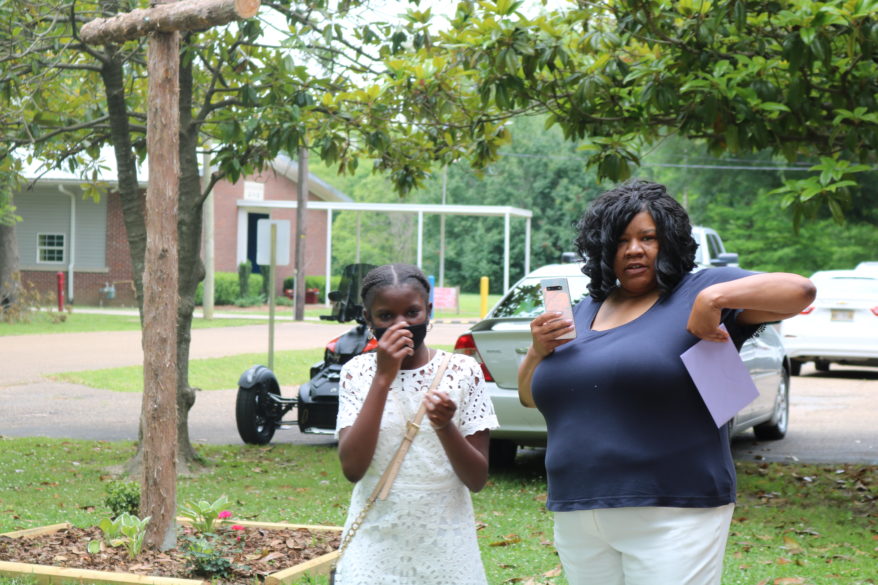

On hand for most of the production in Canton, Flonzie Brown-Wright, a self-described “non-crier,” was moved to tears during depictions of herself, young Bertha Bowman and friend Mamie Chinn.

“She was so special to me. This morning, … when I saw the little girls sitting on the porch, I just lost it. I just lost it because it was just so reminiscent of what actually happened during those days,” said Brown-Wright.

The crew filmed re-enactments at the Bowman family home on Hill Street in Canton, complete with a 1936 Grand Master roadster car parked out front. Scenes with Thea, Brown-Wright and Chinn eating cookies on the front steps, playing with dolls and socializing were filmed with local talent.

Eleven-year-old, Madison Ware of Canton was chosen to play young Bertha. “I was really excited to do the part of Thea,” said Ware.

In addition to scenes at Holy Child Jesus Canton and playing outside the Bowman family home, Ware also re-enacted young Bertha’s hunger strike after her parents forbade her to go off to Wisconsin to become a nun. Ware sat at the dining room table in the Bowman home with determination stating as young Bertha would – “I’m not hungry.”

Other scenes depicted in Canton include portrayals of young Thea, Brown-Wright and Chinn walking to school and playing dress up as nuns.

In Jackson, the crew sat down with Bishop Kopacz at the Cathedral of St. Peter the Apostle to talk about the cause for Sister Thea and spoke about what he called “her first miracle,” when she addressed the U.S. Bishops Conference in June 1989 and led them to join arms and sing “We Shall Overcome.”

At Sister Thea’s grave site at Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis, the crew arranged for a beautiful white spray filled with gardenias, roses and magnolias to sit at her plot. Re-enactment at the grave site included prayer and a hymn led by Myrtle Otto – “I’ll Be Singing Up There.”

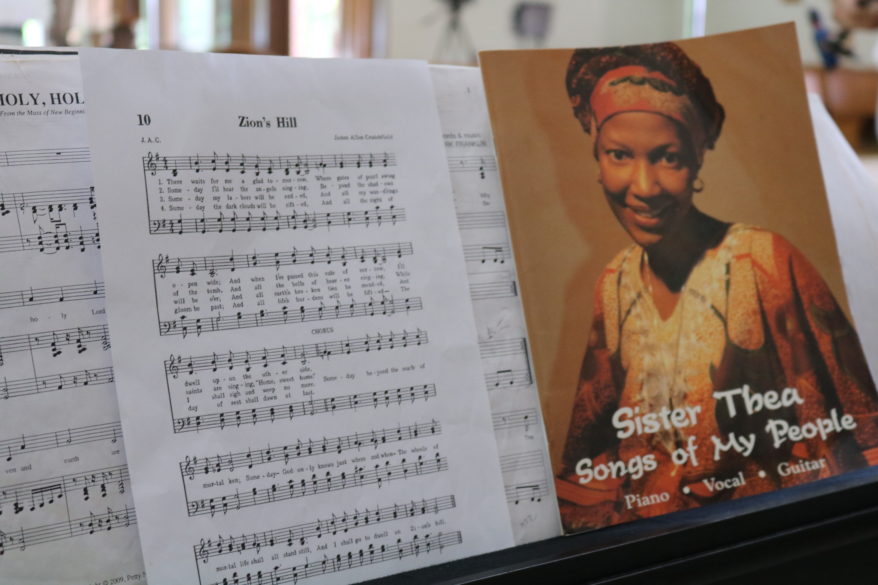

The final day of filming in Canton concluded at Holy Child Jesus with Mass, a performance by the church choir and solo of “On Zion’s Hill” by Wright-Brown.

Life-long friends, Brown-Wright kept in contact with Sister Thea up until her passing from cancer in 1990 traveling from her home, at the time, in Ohio just two weeks before her death. She said Sister Thea told her “what I want you to do when I’m gone … [is] to come back to play and sing the song “On Zion’s Hill.” The same song Sister Thea sang at both her father and mother’s funerals.

With Wright-Brown in an African dashiki and headdress singing there was hardly a dry-eye between the crew present, as Sister Thea’s presence was felt in the moment.

Between June 20-23, the crew filmed in LaCrosse, Wisconsin at St. Rose Convent and Viterbo University, shooting re-enactments of Sister Thea at the FSPA motherhouse. Director Chris Salvador described plans to capture Sister Thea arriving at the convent in a white pinafore dress and then using a machine to morph her. “So, it goes in 360° and she changes from her first outfit, and she eventually comes out in her African dashiki,” said Salvador.

Brown-Wright reminisced during filming in Canton about one trip to LaCrosse to visit her friend. When she got there, Brown-Wright expected to see her friend dressed in a habit, but instead found her in “a dashiki, sandals and a natural.”

“I asked her what happened, and she said, ‘Girl, those petticoats were just too hot,” laughed Brown-Wright. “What she was doing was preparing a culture for a yearning to understand our culture. That was her transformation from coming out of the habits … to her natural dress because that’s who she was,” said Brown Wright.

“She taught the world how to be a Black Catholic sister.”

In New Orleans the film crew will conduct more interviews and film at the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University, where Sister Thea offered courses in African American literature and preaching.

The working title of the film is “Going Home Like a Shooting Star – Sister Thea Bowman’s Journey to Sainthood.” It is drawn from a quote attributed to Sojourner Truth. When Sister Thea was asked what she wanted said at her funeral, she answered,” Just say what Sojourner Truth said: ‘I’m not going to die, honey, I’m going home like a shooting star.’”

Production of the documentary was delayed about a year due to COVID. The film makers, with Bishop Kopacz as executive producer, hope to air the documentary nationwide in the fall of 2022 on ABC.

From the Archives

By Mary Woodward

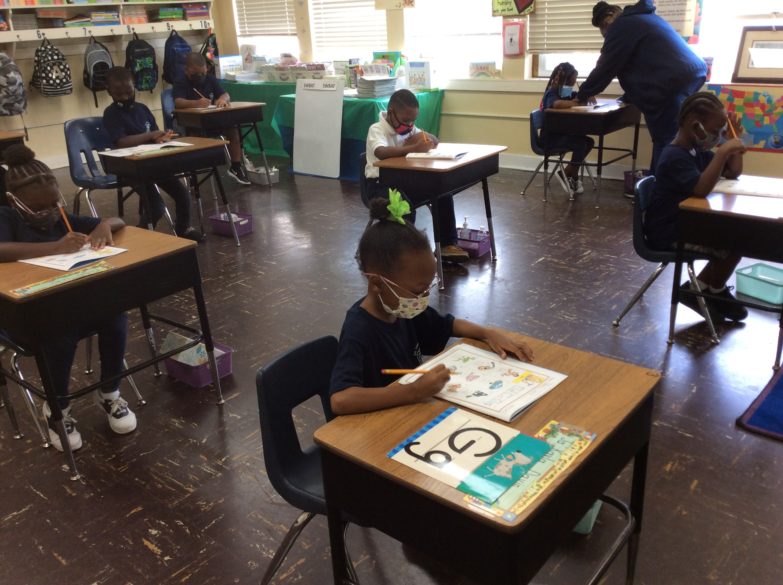

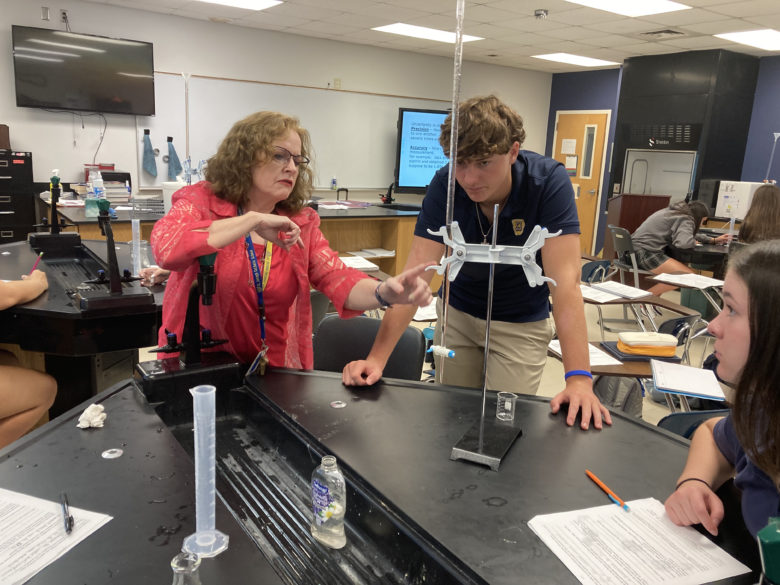

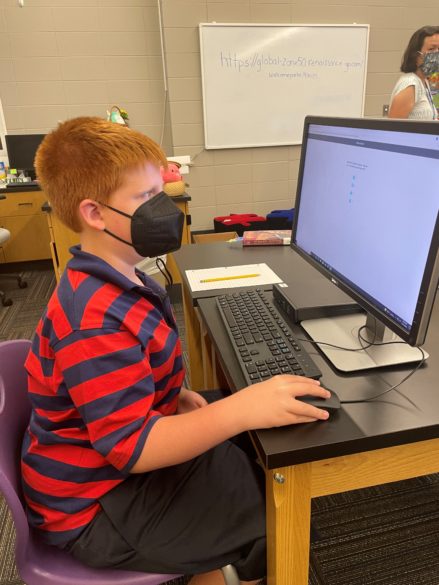

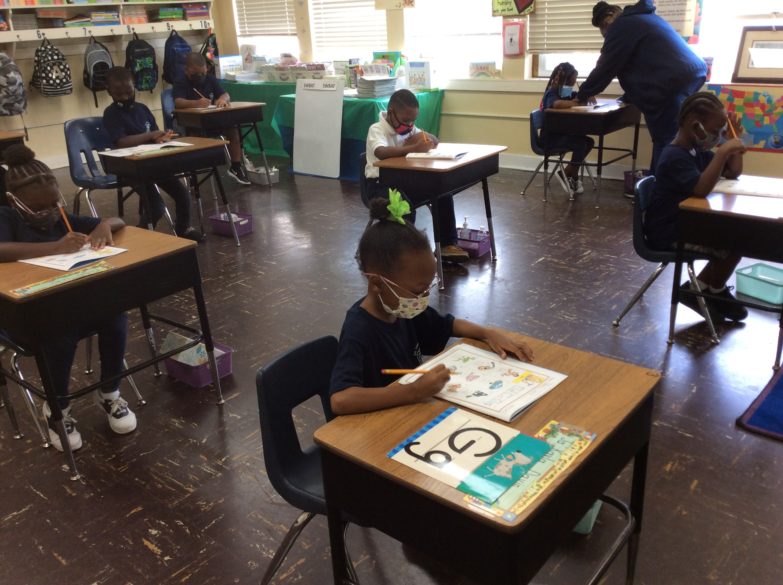

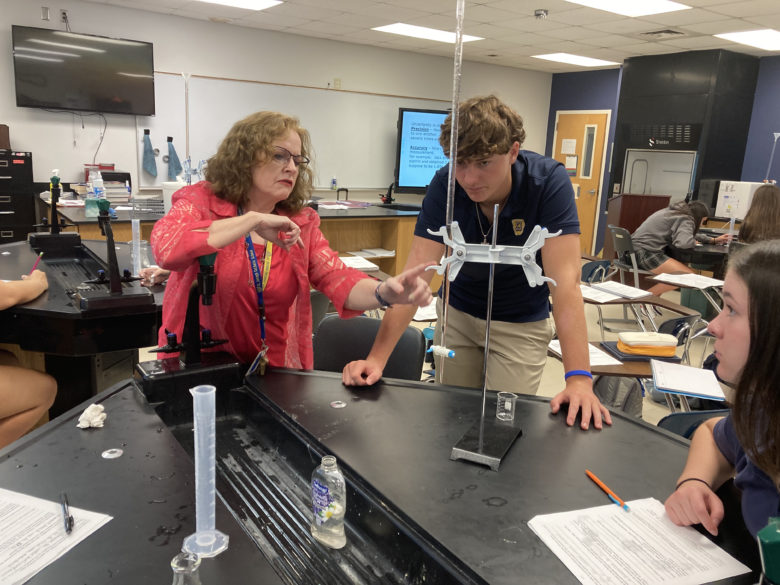

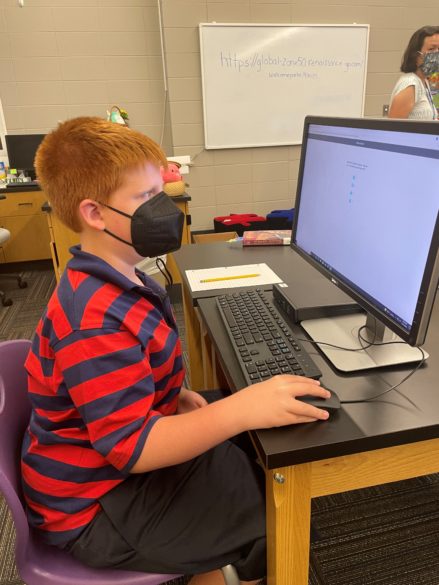

JACKSON – A bishop’s life is full of travel around the diocese to visit parishes, schools and missions. This time of year, it involves school masses for the opening of the new academic year. Because of COVID, these celebrations did not occur last August.

Confirmation celebrations have Bishop Joseph Kopacz all over the diocese from one end to the other. These celebrations normally take place between Easter and Pentecost, but due to schedules and once again the pandemic, Confirmation celebrations have been spread out into the summer months.

This weekend Bishop Kopacz will be in Ripley at St. Matthew Mission to confer Confirmation on more than a dozen young people. Ripley is in Tippah County, and I have a special connection to the area because my maternal grandmother’s family is from Tippah County. My great-grandparents are buried in the Pine Hill Cemetery just outside of Ripley on the way to Walnut.

Suffice it to say that our diocese being the largest diocese geographically east of the Mississippi River creates long drives. Tippah County borders Tennessee and is part of the rolling hills section of the state where beautiful views can be found around various bends in the road. Ripley is close to a four-hour drive from Jackson.

Imagine travelling to Ripley on horseback or in a cart from Natchez as was done in the early days of our diocese. This was the life of our bishops back in the day even up into the early 1900s when Bishop Thomas Heslin was making his way around the diocese for Confirmation celebrations.

Let me share a particular instance from Bishop John Gunn’s diary dated June 8, 1912, in which he accounts for an unfortunate incident that led to Bishop Heslin’s ultimate demise. It may give a better appreciation for a bishop’s life on the road.

“Visit to Montpelier. This is a little mission chapel about 13 miles from West Point, without a railroad and with the poorest roads imaginable. On the way out from West Point to Montpelier I heard a story about Bishop Heslin which is worth recording.

“The good Bishop was, like myself, going out to the little chapel to give Confirmation. The best pair of mules in the neighborhood were commandeered to bring the Bishop out. The Bishop’s carriage was a spring wagon and a plank put over the sideboards formed the cushions for the driver and the Bishop.

“The roads were of that peculiar type known in Mississippi as ‘corduroy’ roads. Branches of trees, stumps, logs, etc. are imbedded in the mud roads during the Winter, In the Spring these are covered with dirt and there is a good road until the first rain comes. Then the dirt is washed up and the stumps are very much in evidence, especially when the mules get into a trot.

“It seems that on the past visit of Bishop Heslin, the driver talked all he knew about cotton, lumber, and the country and talked so much that the mules fell asleep. It is thought that Bishop Heslin – if he was not asleep, was at least nodding – and at the moment the driver woke up and commenced to whip the mules into some kind of activity.

“The sudden start caught the Bishop unprepared and he made a double somersault over the spring wagon and fell on the road. The driver was so busy with the mules that he forgot the Bishop and did not know of the mishap for nearly half a mile.

“Then there was the difficulty of turning the pair of mules on the road and a convenient turning spot had to be reached. This delayed the recovery of the Bishop for a considerable time and when the mule driver and his mules found the Bishop – Bishop Heslin was in a dead faint.

“The good Bishop was a big man and a heavy man, and the mule driver was lean and lanky and there was no help in sight or available. There was nothing to do only to take the sideboards from the wagon and form an inclined plane and roll the Bishop up the plane and make him comfortable in the wagon. “He recovered consciousness before he reached West Point.

“It is said that the Bishop never really recovered from the shock and the injury sustained by this fall.

“The driver who brought me out to Montpelier was the same one who had brought Bishop Heslin and he gave me the story as written.”

This incident would have occurred most likely in 1910 because Bishop Heslin died in February 1911.

Bishop Gunn concludes his description of his own arrival and visit in Montpelier thusly: “I arrived at Montpelier for supper. The day was hot, and all the neighbors of the little village were invited to sup with me.

“There was a table spread for all comers on a kind of porch. The neighbors supplied the feed and there was plenty of it. I think that all the flies of the country got notice because they were present like the locusts of Egypt. They were in everything, tasting everything, and lighting everywhere, especially on the bishop’s nose.

“A few girls got branches of trees and used them to keep the flies away. It was all right as long as the girls minded their business but when they forgot the flies and hit the guests there was some embarrassment.

“We had Mass and confirmation in the little chapel, which strange to say was dedicated to St. Patrick and for that reason several parts of it were painted green. We returned to celebrate Sunday.”

More from Bishop Gunn next time…

(Mary Woodward is Chancellor and Archivist for the Diocese of Jackson)

By Joanna Puddister King

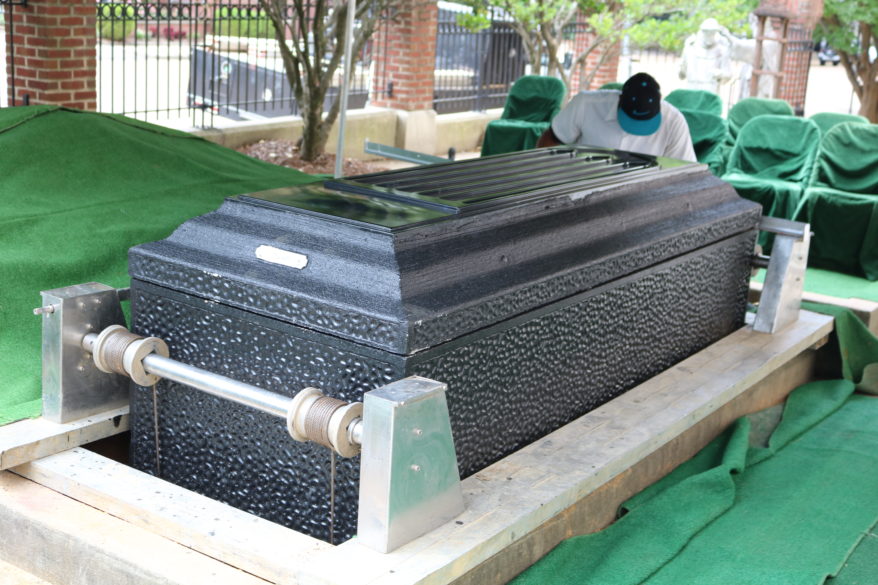

JACKSON – The late Bishop Emeritus Joseph N. Latino, retired bishop of Jackson, who died May 28 at the age of 83 is remembered as a gentle and humble shepherd.

A native of New Orleans, Bishop Latino was ordained a priest for the Archdiocese of New Orleans at St. Louis Cathedral on May 25, 1963. During his priesthood, Bishop Latino served in parishes in New Orleans, Metairie, Houma and Thibodaux. When the Diocese of Houma-Thibodaux was formed in 1977, he remained in the new diocese and served in many capacities including chancellor and vicar general. In 1983, Pope John Paul II named him a Prelate of Honor with the title of Monsignor.

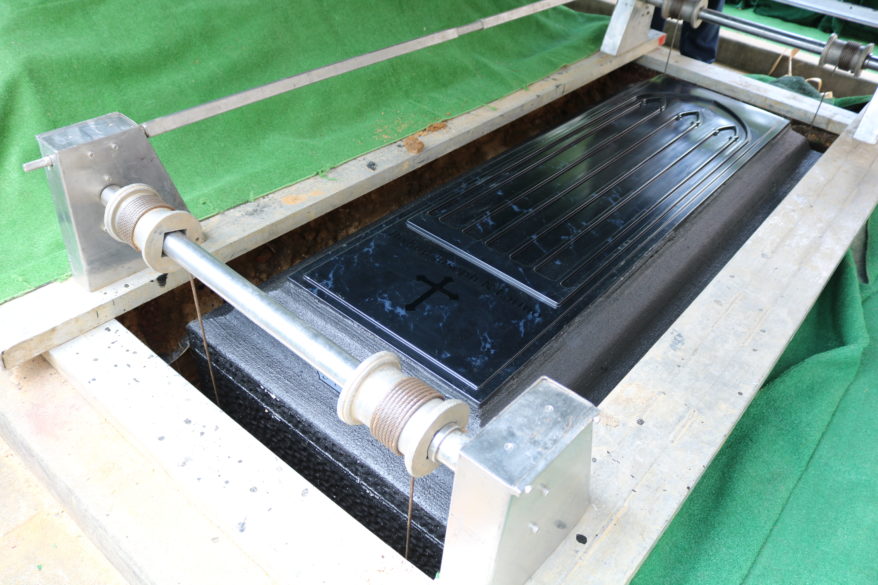

He was appointed the 10th Bishop of Jackson on Jan. 3, 2003 and was installed on March 7, 2003 in the Cathedral of St. Peter the Apostle in Jackson, the place of his final resting place.

Msgr. Elvin Sunds, who served as vicar general for nine years under Bishop Latino and enjoyed his friendship for many years afterward, described him as a “humble, gentle and kind bishop.”

In his homily at a prayer vigil for Bishop Latino on June 8 at the Cathedral, Msgr. Sunds spoke about Bishop Latino’s episcopal motto – Ut Unum Sint – “that all may be one.”

The motto came from the Gospel passage of John that was read at the vigil, explained Msgr. Sunds. “In that Gospel Jesus is praying for his disciples, and he also prays, ‘For those who will believe in me through their word, that they may all be one, as you, Father, are in me and I in you, that they also may be in us.’”

“Jesus’ prayer is that through the proclaiming of the Gospel, may we all share together in the life of God as one. That was the motto and the focus of Bishop Latino’s episcopal ministry. He wanted all of us to be one in Christ Jesus. He promoted that unity in Christ,” said Msgr. Sunds.

During his years as bishop, Bishop Latino fostered Gospel-based social justice initiatives, lay leadership and vocations. During his tenure the office for the Protection of Children was established to help insure a safe environment for children in our churches, schools and communities.

Msgr. Sunds described Bishop Latino’s social justice work mentioning that he publicly addressed such issues as racism, the rights of immigrants, care for the poor, the death penalty, and the right to life of the unborn during his tenure.

Bishop Latino’s nephew and godson, Martin Joseph Latino delivered remarks about ‘Uncle Joe’ at the vigil service sharing stories of humor, of mystery and a little bit about his favorite movie “A Man for All Seasons.”

It is still as mystery to Martin Latino how his Uncle Joe was able to call him in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. At the time, Latino was the chief director of safety and was with the Mandeville Fire Department. With all of the cell towers down in the area, no one was able to receive any calls, but Uncle Joe got through.

“His message to me that day was don’t lose heart. Work hard. Restore your community. Be a leader and keep everyone safe. … I still to this day do not know how he was able to get through,” said Latino.

In attendance at the Mass of Christian Burial on June 9, were bishops from around the region with Archbishop Thomas J. Rodi of the Archdiocese of Mobile as celebrant, along with the priests of the Diocese of Jackson, seminarians, deacons and the people of the diocese. In his opening remarks, Archbishop Rodi extended his sympathy to Bishop Latino’s family, Bishop Joseph R. Kopacz and the people of the Diocese of Jackson.

“We gather here in sorrow over the loss of a powerful presence of a good man, a good priest, a good bishop, who in so many ways in his ministry blessed the people first in Louisiana, then in Mississippi,” said Archbishop Rodi.

During his homily at the funeral Mass, Bishop Kopacz recollected his first encounter with Bishop Latino seven and a half years ago at the Jackson airport. He recalled Bishop Latino smiling “to know he had a successor that was real,” laughed Bishop Kopacz. From that point the two grew in their friendship over the years and he shared stories of Bishop Latino’s background and interactions they had over the years through his last one hours before Bishop Latino’s death.

“My final encounter with Bishop Latino was sitting at his bedside within hours of his death, softly saying the rosary and praying … as he slowly passed from this world to the next. I spoke the words that he no longer could,” shared Bishop Kopacz.

He also gave thanks for Bishop Latino’s trustworthy service for nearly six decades, through times of strength and his experiences of accepting the changes in his health.

“In his retirement at times he grieved the physical limitations that prevented him from serving more actively in the diocese. But at the foot of the Cross, his ministry of prayer and presence was a treasure for us. And his early monastic formation served him well in his later years. He could be in that state for prayer and through it all he trusted in the Lord, who called him forth from his youth and in holy fear he grew old in God,” said Bishop Kopacz.

Diocesan chancellor, Mary Woodward also spoke at the vigil service on her special friendship with Bishop Latino, as he lifted up her talents, supported her and mentored her. The two of them, along with Bishop Houck, who passed in 2016, traveled to Rome many times. Woodward described the last trip they had to Rome for an ‘ad limina,’ where they also added a trip to Sicily to the Latino family’s ancestral hometown of Contessa Entellina.

Woodward described Bishop Latino as “energized” by the trip and said that he was excited that he would be able to celebrate a private Mass in the home church of his grandparents. “But when the doors opened the church was packed with the townspeople coming to see this bishop from America,” Woodward mused.

Bishop Latino was always there for her and she for him, making sure he was “ok” until the end of his earthly life, just as the women in the Gospel wanted to do for Jesus.

Most did not know that Bishop Latino was in constant pain for the last 40 years. “He had nerve pain in his legs and it never subsided,” said Woodward. “He bore that Cross with such grace and elegance.”

Through many surgeries over the years to help relieve the pain, Woodward often felt like a “cheerleader” who was there to “help him carry the Cross.”

“And that last day, … I felt like I went from helping him carry the Cross to being at the foot of the Cross. … It was a beautiful witness to ‘I’m in God’s hands. God’s going to take care of me. It’s ok,’” said Woodward who was with Bishop Latino up until his passing.

“I don’t ever think that I could say in a few minutes the profound impact he has had on me and on all of us.”

Woodward also took great care in organizing Bishop Latino’s vigil and Mass of Christian Burial, making sure all elements he wanted were included. As an “opera aficionado,” Woodward made sure to include some opera. During the vigil, Woodward included a piece from Cavalleria Rusticana by Pietro Mascagni. The significance being that Bishop Latino would come in most mornings into their shared office humming that tune. She even had to step away during the vigil upon hearing it.

“The witness of his life, the witness of him carrying that pain was something that strengthens me and I feel very privileged to have been able to walk that journey with him. I will be forever changed,” said Woodward.

“Well done, good and faithful servant.”

By Joanna Puddister King

JACKSON – From an early age, Andrew Bowden had a heart for service. On May 15, he continued that call as he was ordained a transitional deacon at his home parish of St. Jude in Pearl. He will serve as a deacon until ordination to the priesthood next year.

“The first time that I remember him saying anything about wanting to be a priest, he was about kindergarten age,” said his mother, Rhonda Bowden, who coordinates liturgy and pastoral care at St. Jude.

Deacon Bowden recalled attending a Mass around that age, celebrated by Bishop William Houck, that sparked his interest in religious life.

“He had an incredibly powerful voice, and I was impressed by him. So impressed that the next time I saw my pastor, Father [Martin] Ruane, I announced to him that I wanted to be a bishop,” laughed Deacon Bowden.

Father Ruane, who passed in 2015, was a great influence on young Bowden. His sense of humor, humble nature and his joy were attributes that Bowden wanted to emulate. “I don’t remember exactly how he responded to the four-year-old declaring that he wanted to be bishop, but he was able to replace that idea … with the desire to become a priest,” said Deacon Bowden.

Around the same time, Bowden also started talking about wanting to be an altar server. Although Father Ruane’s policy was that alter servers must be in the fourth grade, he graciously did an abbreviated training session just for Bowden in the third grade, shortly before he left St. Jude for a new assignment.

“Altar serving then became a major part of my pre-discernment,” explained Deacon Bowden. “Through altar serving at St. Jude as I grew up, I began to love God, the church and the priesthood in a much deeper way.”

Bowden was also actively engaged in St. Jude’s youth group and enjoyed sharing his faith and teaching the younger altar servers.

His mother, Rhonda couldn’t recall any other possible vocation or career path her son ever mentioned, other than around four years old saying that he wanted to be an architect priest who would build churches and work in the church, imagining as only a child can, to also build underground tunnels to his house so that he could eat lunch with her every day.

By the end of high school, Deacon Bowden strongly felt he was being called to the priesthood. Father Jeffrey Waldrep, who was pastor at St. Jude in Bowden’s high school years inspired his interest in liturgy and was helpful to him as he entered the formal discernment process for priestly formation.

His parents were extremely supportive of his desire and after graduating from Brandon High School in the spring of 2014 he completed his application for the seminary just as Bishop Joseph Kopacz arrived in the diocese.

“We strongly encouraged Andrew to have a ‘backup-plan’ in case the new bishop was not eager to send an 18-year-old to seminary college. [But], he was adamant that God’s will would prevail, and that God would make a way for him. And God did,” said Bowden’s mother.

Bowden spent four years at St. Joseph Seminary College in Covington, Louisiana and moved on to Notre Dame Seminary, where he just completed his third year before being ordained a transitional deacon on May 15.

“During the diaconate internship we try to place our men in parishes that will give them a wide range of experiences,” said Father Nick Adam, director of vocations, who first met Bowden in high school, while he was in seminary school.

“This will be the first time a seminarian baptizes a baby, witnesses a wedding or presides at a funeral, and we want to make sure they have plenty of opportunities to dive into parish life and walk with families in this way.”

Those in the transitional diaconate are also tried to be place at a parish with a school so they can be a part of the day-to-day life of the kids and faculty. A great place for that is at St. Mary Basilica and Cathedral School in Natchez, and Bowden is looking forward to his service to the community.

“During seminary, I have greatly missed the local expression of the church that is the Diocese of Jackson. I am greatly looking forward to spending the next few months in Natchez with Father [Scott] Thomas and Father [Mark] Shoffner. … It will be so good to get to know people there and learn how I can serve them best,” said Deacon Bowden.

During his diaconate ordination, Bowden’s mother cried ‘happy tears.’ “Seeing my son so happy and knowing that he was responding to God’s call made my heart sing with joy.”