(Editor’s note: A story about this research project appeared in the March 23 edition of Mississippi Catholic.)

By Tim Muldoon

CHICAGO (CNS) – When Pope Francis addressed the U.S. Congress Sept. 24, 2015, he pointed to the witness of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., suggesting that a great nation “fosters a culture which enables people to ‘dream’ of full rights for all their brothers and sisters.”

As we remember the 50th anniversary of his assassination, it is important to recall the hard work of social change that helped bend our nation in the direction of greater justice. The integration of Catholic parishes and schools in Mississippi provides an important window into the moral struggles that existed inside the church’s own institutions, and offers us lessons for today.

JACKSON –The August 6, 1964 letter issued by Bishop Gerow to be read at all parishes announcing that Catholic schools would accept all children, regardless of race, resides in the Diocese of Jackson archives. (Photo by Tereza Ma)

In the decade between 1955 and 1965, Mississippi was a hotbed of racial unrest, and Catholic schools and parishes were not immune. It was a period sandwiched between two racially motivated murders that drew national attention: the murder of the 14-year-old boy Emmett Till in 1955 and the Freedom Summer (or “Mississippi burning”) murders of three young civil rights activists in 1964. In Catholic parishes, groups of whites threatened blacks attending Mass at St. Joseph in Port Gibson; Sacred Heart in Hattiesburg; St. Joseph in Greenville; and many others.

Bishop Richard Oliver Gerow, head of what is now the Jackson Diocese, had been nurturing hopes for desegregation of his parishes and schools for years, keeping meticulous files of racial incidents. A realist, he understood that episcopal fiat could not undo generations of racial prejudice, and so worked slowly to develop collaborators.

One example in 1954 was in Waveland, where a parishioner threatened black priests sent by Father Robert E. Pung, a priest of the Society of the Divine Word, who was the rector of St. Augustine Seminary, the first black seminary in the United States. Father Pung composed a strongly worded letter to the man:

“And what did the priest come to your parish to do: just one thing – to celebrate Mass and bring Christ down upon your parish altar and to feed the flock of Christ with his sacred body. And that the majority of the parishioners looked upon the priest celebrating holy Mass as a priest of God and not whether he was colored or white is evident from the fact that last Sunday over three Communion rails of people received holy Communion from his anointed hands.”

He assured the man that these same priests would be praying for him.

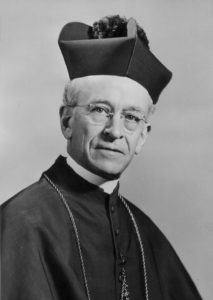

Bishop Richard O. Gerow, pictured in an undated photo, headed what is today the Diocese of Jackson, Miss., from 1924 to 1967. He was a strong advocate of desegregation for Catholic parishes and schools in his diocese but in such racially charged times he promoted incremental change, to protect black priests and parishioners from retaliation. (CNS photo/courtesy Diocese of Jackson Archives via Catholic Extension) See RACIAL-DESEGREGATION-MISSISSIPPI April 6, 2018.

Bishop Gerow kept an extensive file including this and many other racial incidents. In an entry from November 1957, he shares the advice he gave to a group of Catholic men who were distressed at the ill treatment of black parishioners. He wrote:

“We are facing a situation in which we as a small minority are up against a frantic and unreasonable attitude of a greater majority of the community. If we attempt to force matters, we are liable to do injury not only to ourselves but also to those whom we would wish to do help, namely, the Negroes. Imprudent action on our part might cause them very serious even physical harm.”

His position on desegregation was a delicate one, which attempted to balance a complex array of factors and forces:

• First, there were the pastoral needs of black Catholics in the region, some of whom had to travel to celebrate the sacraments and who sometimes faced verbal or physical threats.

• Second, there were the established parishes comprised mostly of whites, themselves a minority in a region that was dominated by Protestants.

• Third, there were men in both state and local government, not to mention law enforcement, who were sometimes hostile even to white Catholics, and so the presence of blacks in Catholic congregations was a further potential danger.

• Fourth, there were a growing number of organizations supporting the cause of integration: organizations such as the NAACP and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, as well as Catholic organizations, like the National Catholic Welfare Conference and the National Catholic Conference for Interracial Justice, or NCCIJ.

In 1963, Henry Cabirac Jr. of the NCCIJ began to force the hand of Bishop Gerow, when Cabirac called for integration of schools at meetings in Mississippi City. Responding to Cabirac’s advocacy that black families apply for admission to white Catholic schools, Bishop Gerow wrote in his diary of July 1 the following:

“My point is this: School integration is going to come in the course of time, but at present we are not ready for it. I feel that the first step is to create a better relationship between the two races.”

He wrote guidelines for sermons to be preached throughout the diocese on the moral demand of integration, but remained convinced that school integration would be dangerous for black parishioners. Nevertheless, only two days after this entry, on July 3, the bishop wrote that he had received letters from two black families requesting admission of their children to schools “which we have considered white.” He laments being in an embarrassing position, feeling that “a bit more preparation of our whites is prudent.”

No doubt the bishop was sensing great tension in the air. Only two weeks earlier, the field secretary for the NAACP, Medgar Evers, had been assassinated, and once again the nation’s attention was on Mississippi. The immediate aftermath of the assassination saw Gerow in a political role to which he was naturally averse.

He had been active in drawing together white ministers in the various churches in Jackson for some time, and in fact had arranged for a meeting that included black ministers only five weeks earlier. The groups had hoped that their combined voices might thaw the icy relationship between blacks and the Jackson Chamber of Commerce. But after the assassination, the bishop felt compelled to make a public statement which he shared with the press.

The opportunity to act decisively happened one year later, July 2, 1964, when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed into law the Civil Rights Act. Bishop Gerow issued a statement to the press the next day.

“Each of us, bearing in mind Christ’s law of love, can establish his own personal motive of reaction to the bill and thus turn this time into an occasion of spiritual growth. The prophets of strife and distress need not be right.”

On Aug. 6, the bishop published a letter to be read in all churches the subsequent Sunday (Aug. 9), indicating that “qualified Catholic children” would be admitted to the first grade without respect to race. He called on all Catholics to “a true Christian spirit by their acceptance of and cooperation in the implementation of this policy.” In a letter to his chancellor, Bishop Gerow describes this move as “more in accord with Christian principle than of segregation.” The following year, he desegregated all the grades in Catholic schools.

In recent months, we also have seen tragic examples of racially motivated hate crimes. Later this year, the U.S. bishops plan to release their first pastoral letter on racism in nearly 40 years. Mindful of the gifts that people of all races bring to the community of faith, and of the need to work towards a just social order, the president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, Cardinal Daniel N. DiNardo of Galveston-Houston, said at the launching of the racism task force last August, “The vile chants of violence against African-Americans and other people of color, the Jewish people, immigrants, and others offend our faith, but unite our resolve. Let us not allow the forces of hate to deny the intrinsic dignity of every human person.”

For ore than a hundred years, Catholic Extension has been serving dioceses with large populations of the poor, the marginalized and people of color, and have sent millions of dollars to ensure that they have infrastructure and well-trained church leaders that will form them for positive social change. Our dream is that these leaders will, in the words of Pope Francis, “awaken what is deepest and truest” in the life of the people, and ultimately be the catalyst of transformation in their communities.

During this 50th anniversary of Rev. King’s assassination, we are mindful of all those Christians who have gone before us in the struggle for a more peaceful and just society, so that we may be inspired by their example to confront and struggle with the pressing questions of our day. Bishop Gerow’s extensive efforts to chronicle the important period of his episcopacy remind us that we, too, live in the midst of a history that others will remember and judge in the light of God’s call to live justly.

(Tim Muldoon is director of mission education for Catholic Extension. Contributing to this article was Mary Woodward, chancellor of the Jackson Diocese, who assisted with the Bishop Gerow archive.)